About the Book

On my desk, behind the tub of paper clips and the collection of coffee mugs I have yet to return to the kitchen, is a small ceramic bust of a woman's head. The skull is smooth and crisscrossed with a network of dark blue lines demarking the various regions of the brain--with labels like "Ideality," "Acquisitiveness," and "Region of the propensities common to man and the lower animals." In addition to serving as a model for eager, young phrenologists anxious to divine personality from the shape of the head, my ceramic sculpture opens at the breastbone so that it can be used as an inkwell. It sits as a source of inspiration, not ink, turned just enough so that the unpainted eyes do not regard me as I'm writing.

The colorful history of medicine has intrigued me ever since I looked up "phrenology" in the dictionary and marveled that reading human characteristics in the contours of the skull was once common belief. What other (now discredited) medical ideas have we held, I began to wonder. I poured through the works of Jan Bondeson, Carl Zimmer, and several other medical historians and science writers who tell captivating tales of practices that read like fiction: curative radium, lobotomy, therapies requiring ground millipede and mercury. These techniques and the contemporaneous debates about life, death, and the soul took hold of my imagination. Who were the people who believed humans could birth rabbits? Or that routine bleeding could cure the common cold? I began to look at how doctors and the medical philosophies of previous generations impacted daily life.

While doctors of the eighteenth century argued whether a lack of respiration and pulse confirmed expiration, common people worried that they would be buried alive. Despite diagnostic tools like tobacco-smoke enemas, applications of electrical current, and careful examinations of the eye for softening and drying, patients amended wills to request delays before burial and demanded that their coffins be out fitted with bells and speaking trumpets. No one knew exactly when the soul left its mortal coil and many agonized. The potentially dead lay on tables for days awaiting putrefaction, the only certain symptom of death.

Similar uncertainty surrounded the soul and its relationship to the body. Did the soul cause the pineal gland to quiver, as Rene Descartes believed? Or did it reside, as Galen proposed, in the liver and heart as well as the head, comprising a cocktail of spirits that caused disease, even madness, when out of balance? Philosophers struggled to link the spiritual to the physical, but their understanding of the human body was primitive. Galen's anatomy, which was accepted well into the seventeenth century, was based on studies of "lower" animals: the brain of a cow, the uterus of a dog, the kidneys of a pig. Doctors endeavored to cure ailing patients, but they did not even know the true shape of the organ that, perhaps, housed the troubled soul.

As I learned more, I journeyed through a history that was both fascinating and foreign; I watched theories develop and technologies advance; I watched our knowledge of the human body grow and our ideas of how best to treat illness shift and change. I saw why a man might choose to drill a hole in his head, and why a woman might decide to insert and remove silicon implants.

Today, we continue to discuss how to diagnose and define life and death. In court, lawyers argue for and against pulling feeding tubes from patients in persistent vegetative states. Healthy people worry that signing up as an organ donor will lead to premature termination. And the debate about the soul and its relationship to human tissue is fundamental to conflicts that arise over abortion and stem cell research. Advancements in science have not answered the questions doctors posed centuries ago, and though we can sequence genes and associate specific markers with disease, we have not defeated illness.

It is very easy to look back and laugh at how foolish our beliefs seemed. How could we have argued that the brain is no more than phlegm? Or that frogs live in our stomachs? Or that someone could spontaneously combust? We are all limited by the sophistication of our tools and the generally accepted theories of our times. And though the doctors of our generation will do their best to cure us, their practices might horrify or amuse our great grandchildren.

I'm grateful for the science of my times--though perhaps, one day, I will be a character in another writer's story about how we give birth in hospitals, or take insulin for diabetes, or operate on the open heart. I look forward to seeing what we will learn. And despite the (sometimes staggering) mistakes of our past, I will always have a deep respect for the people who contribute to the evolving field of medicine, dedicating their lives to saving others.

Please check back soon for more information about the book, or sign up for the mailing list!

|

|

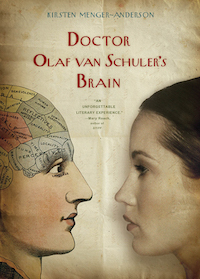

Cover Design: Honi Werner

"Spellbinding ... this book by the gifted new writer Kirsten Menger-Anderson about a family fated to madness, a family of doctors driven by an inner compulsion to heal is like nothing else you've ever read before. It's truly original and impossible to put down."

--Roald Hoffmann, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry and poet/playwright

* * *

"This satisfying and wholly original collection is a true pleasure to read. In seamless prose, Menger-Anderson captures a panoramic New York spanning five centuries, where surgeons and tavern owners, Macy's clerks and suffragettes, gangsters and prison reformers all grapple with mysteries of science and of the soul."

--Daphne Kalotay, author of Calamity and Other Stories

* * *

"If I had a talent for fiction, Doctor Olaf van Schuler's Brain is the book I'd dream of writing. Kirsten Menger Anderson's writing floors me. To read her luminous prose applied to the grotesqueries of the characters is an unforgettable literary experience."

--Mary Roach, author of Bonk, Stiff and Spooked

|